-40%

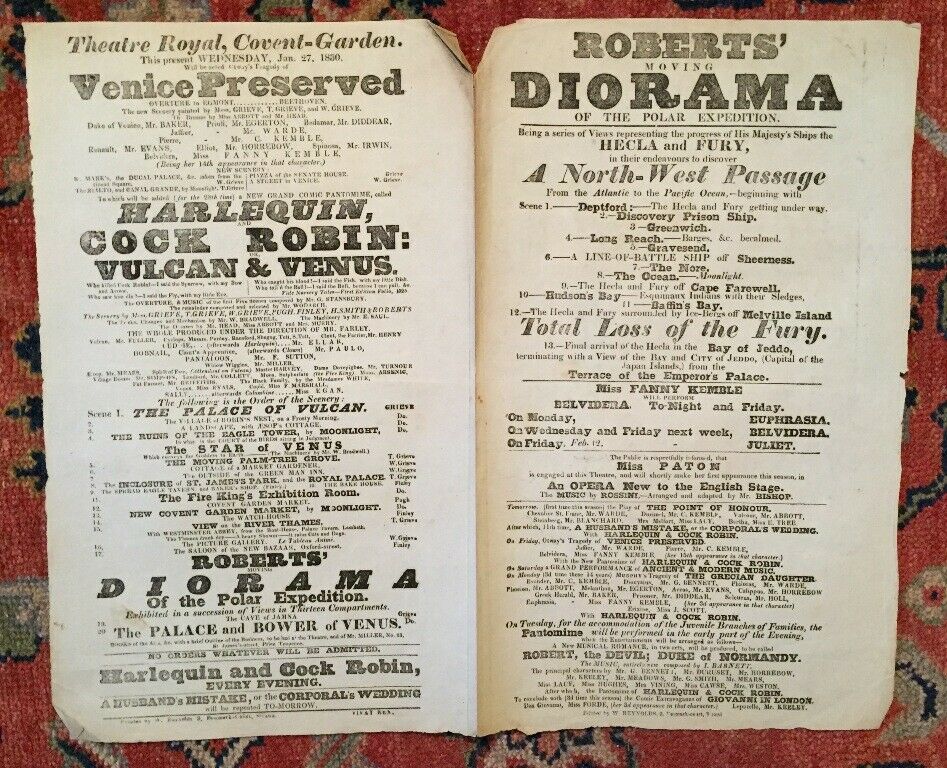

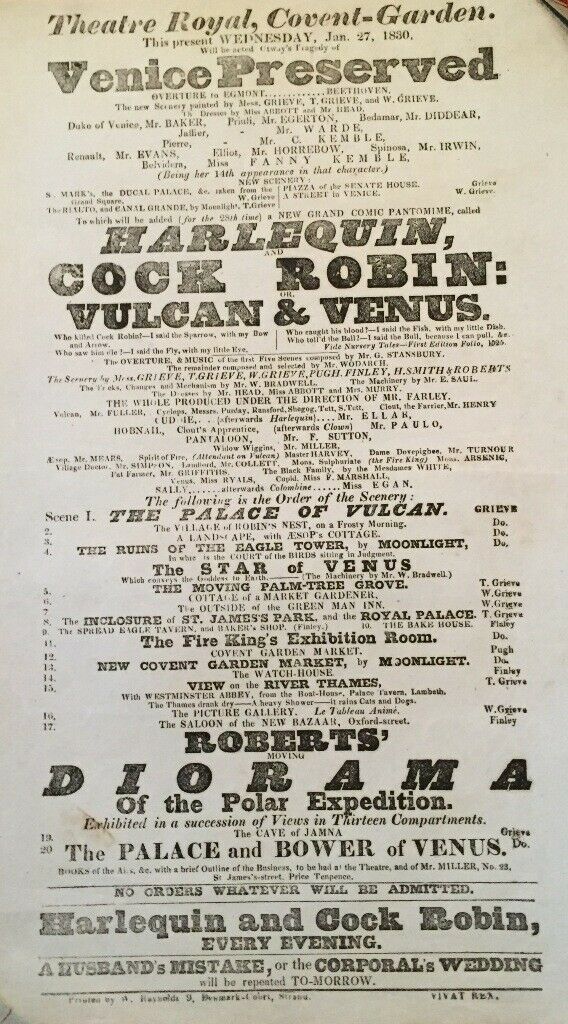

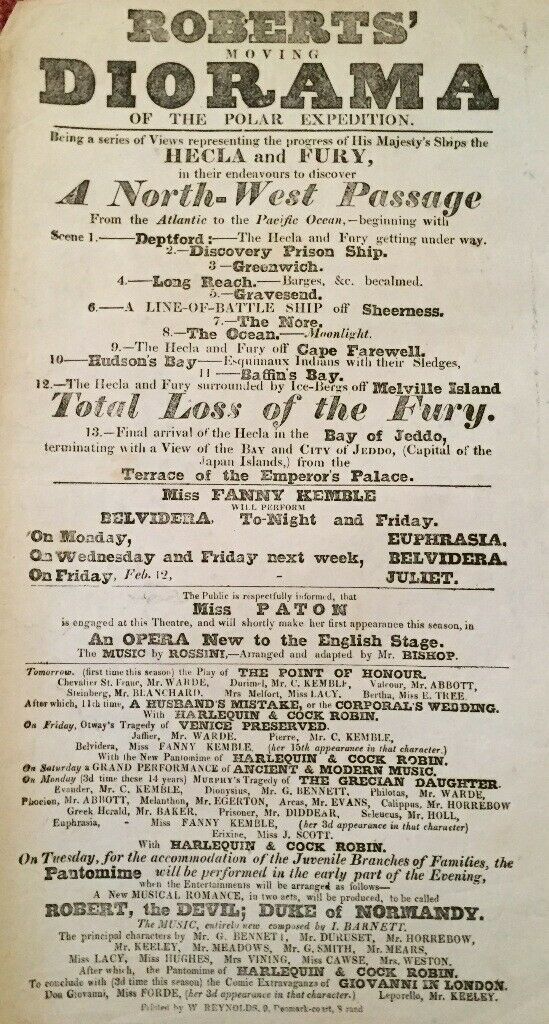

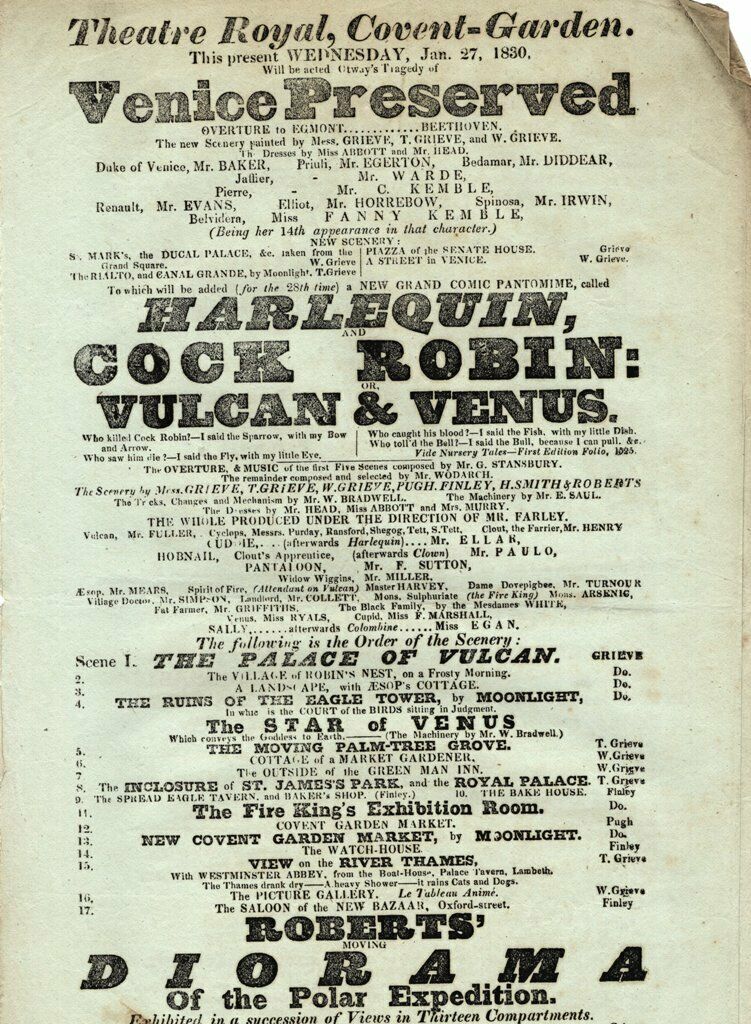

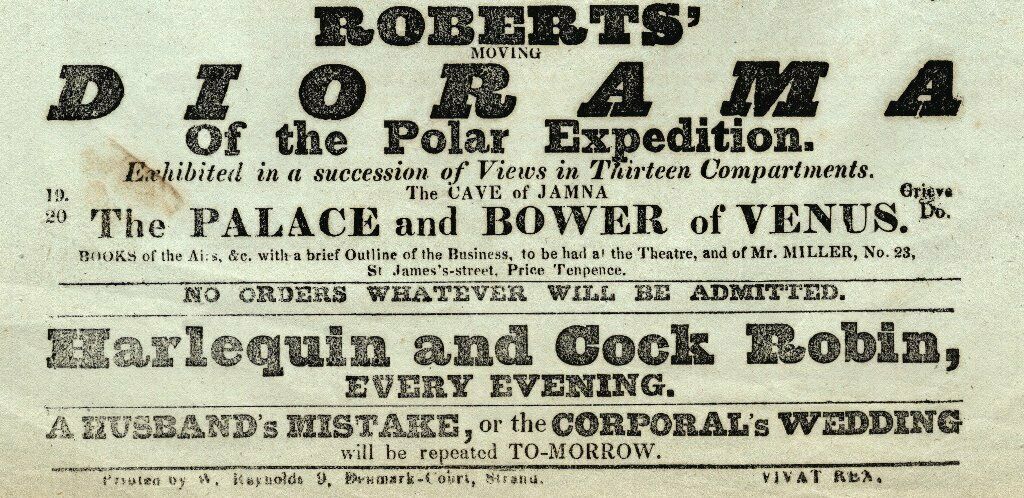

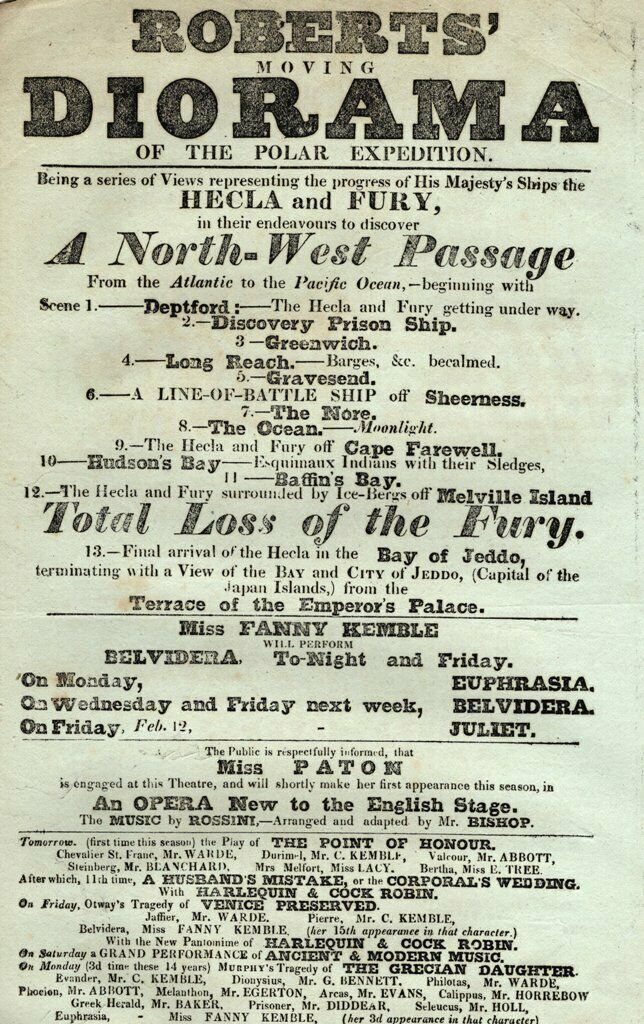

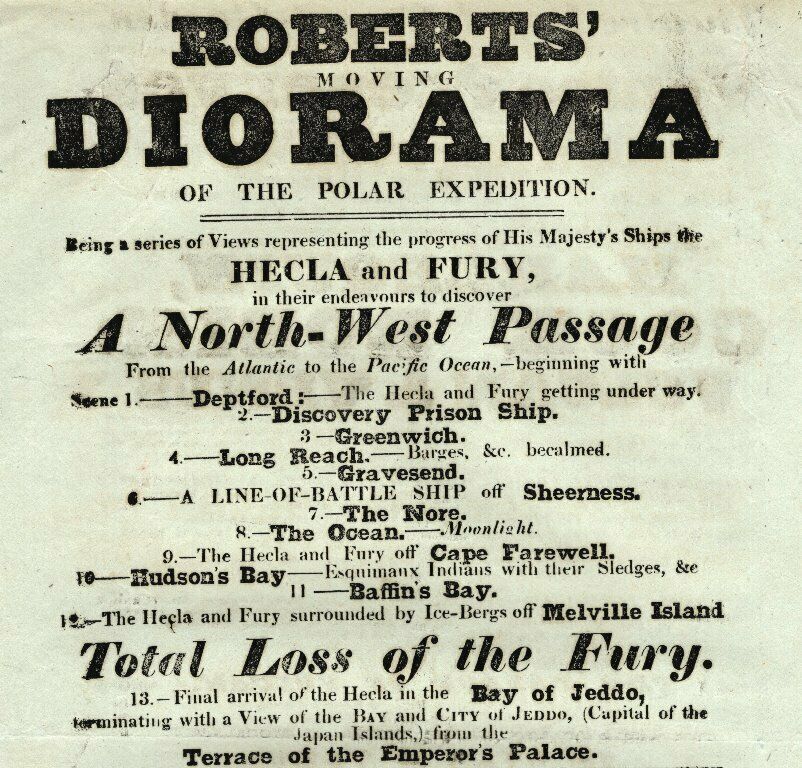

*DIORAMA OF POLAR EXPEDITION & FANNY KEMBLE RARE LARGE 1830 THEATRE BROADSIDE*

$ 105.59

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

A magnificent original double sided January 27, 1830 Theatre Royal, Covent Garden broadside for Fanny and Charles Kemble in Venice Preserved and Roberts' Diorama of the Polar Expedition, documenting the 1825 trip to the Arctic of the HMS Hecla and Fury. With notices for Fanny Kemble in The Grecian Daughter and Romeo and Juliet. Dimensions thirteen and three quarters by seventeen inches. Light wear at top otherwise good. See Fanny and Charles Kemble's extraordinary biographies and the story of the 1825 Polar Expedition below.Ships USPS insured. Shipping discounts for buyers of multiple items. Credit cards accepted with Paypal. Inquiries always welcome. Please visit my other eBay items for more early dance, theatre music and historical autographs, broadsides, photographs and programs and great actor and actress cabinet photos and CDV's.

From Wikipedia:

Frances Anne "Fanny" Kemble

(27 November 1809 – 15 January 1893) was a British actress from a

theatre family

in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and popular writer and abolitionist, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes of memoirs,

travel writing

and works about the theatre.

In 1834, Kemble married a French man,

Pierce Mease Butler

, grandson of U.S. Senator

Pierce Butler

, whom she had met on an American acting tour with her father in 1832. After living in Philadelphia for a time, Butler became heir to the cotton, tobacco and rice

plantations

of his grandfather on Butler Island, just south of

Darien, Georgia

, and to the hundreds of

slaves

who worked them. He made trips to the plantations during the early years of their marriage, but never took Kemble or their children with him. At Kemble's insistence, they finally spent the winter of 1838–1839 there and Kemble kept a diary of her observations, flavored strongly by

abolitionist

sentiment.

Butler disapproved of Kemble's outspokenness, forbidding her to publish. The relationship grew abusive, and Kemble eventually returned to England with her two daughters. Butler filed for a divorce in 1847, after they had been separated for some time, citing abandonment and misdeed by Kemble.

[1]

She returned to the theatre and toured major US cities, giving successful readings of Shakespeare plays. Her memoir circulated in

American abolitionist

circles, but she waited until 1863, during the

American Civil War

, to publish her anti-slavery

Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839

.

[2]

It has become her best-known work in the United States: she published several other volumes of journals. In 1877, she returned to England with her second daughter and son-in-law. She lived in London and was active in society, befriending the writer

Henry James

. In 2000,

Harvard University Press

published an edited compilation from her journals.

These included

Record of a Girlhood

(1878) and

Records of Later Life (1882).

[3]

Youth and acting career

Fanny Kemble as a young girl

A member of the famous Kemble theatrical family, Fanny was the eldest daughter of the actor

Charles Kemble

and his

Viennese

-born wife, the former

Marie Therese De Camp

. She was a niece of the noted tragedienne

Sarah Siddons

and of the famous actor

John Philip Kemble

. Her younger sister was the opera singer

Adelaide Kemble

.

[2]

Fanny was born in London and educated chiefly in France.

[

citation needed

]

In 1821, Fanny Kemble departed to boarding school in Paris to study art and music as befitted the child of the most celebrated artistic family in England at that time. In addition to literature and society, it was at Mrs Lamb's Academy in the Rue d'Angoulême, Champs Elysées, that Fanny received her first real personal exposure to the stage performing staged readings for students' parents during her time at school. As an adolescent, Kemble spent time studying literature and poetry, in particular the work of Lord Byron.

[4]

One of her teachers was Frances Arabella Rowden (1774 – c. 1840),

[5]

who had been associated with the

Reading Abbey Girls' School

since she was 16. Rowden was an engaging teacher, with a particular enthusiasm for the theatre. She was not only a poet, but according to

Mary Russell Mitford

, "she had a knack of making poetesses of her pupils"

[6]

In 1827, Kemble wrote her first five-act play,

Francis the First

. It was met with critical acclaim from multiple quarters. Nineteenth-century critics wrote that the script "displays so much spirit and originality, so much of the true qualities which are required in dramatic composition, that it may fairly stand upon its own intrinsic worth, and that the author may fearlessly challenge a comparison with any other modern dramatist."

[7]

On 26 October 1829, at the age of 20, Kemble first appeared on the stage as Juliet in

Romeo and Juliet

at

Covent Garden Theatre

, after only three weeks of rehearsals. Her attractive personality at once made her a great favourite, and her popularity enabled her father to recoup his losses as a

manager

. She played all the principal women's roles of the time, notably Shakespeare's

Portia

and Beatrice (

Much Ado about Nothing

), and

Lady Teazle

in

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

's

The School for Scandal

.

[8]

[9]

Kemble disliked the artificiality of stardom in general, but appreciated the salary which she accepted to help her family in their frequent financial troubles.

In 1832, Kemble accompanied her father on a theatrical tour of the United States. While in Boston in 1833, she journeyed to

Quincy

to witness the revolutionary technology of the first commercial railroad in the United States. She had previously accompanied George Stephenson on a test of the Liverpool and Manchester, prior to its opening in England, and described this in a letter written in early 1830. The

Granite Railway

was among many sights which she recorded in her journal.

Kemble returned to acting as a solo platform performer, beginning her first American tour in 1849. During her readings she rose to focus on presenting edited works of Shakespeare, though unlike others she insisted on representing his entire canon, ultimately building her repertoire to 25 of his plays. She performed in Britain and in the United States, concluding her career as a platform performer in 1868.

[10]

Marriage and daughters

In 1834, Kemble retired from the stage to marry on 7 June an American, Pierce Mease Butler.

[2]

Although they met and lived in Philadelphia, Butler was the grandson of

Pierce Butler

, a

Founding Father

and heir to a large fortune in cotton, tobacco, and rice plantations. By the time the couple's daughters, Sarah and Frances, were born, Butler had inherited three of his

grandfather's plantations

on

Butler Island

, just south of Darien, Georgia, and the hundreds of people who were enslaved on them.

[11]

The family visited

Georgia

during the winter of 1838–1839, where they lived at the plantations at Butler and

St. Simons

islands, in conditions primitive compared to their house in Philadelphia. Kemble was shocked by the living and working conditions of the slaves and

their treatment

by the overseers and managers. She tried to improve matters,

complaining to her husband about

slavery

and about the

mixed-race

slave children attributed to the overseer, Roswell King, Jr.

[

citation needed

]

Marital tensions had emerged when the family returned to Philadelphia in the spring of 1839. Apart from their disagreements over slave treatment on Butler's plantations, Kemble was "embittered and embarrassed" by Butler's marital infidelities.

[12]

Butler threatened to deny Kemble access to their daughters if she published any of her observations about the plantations.

[13]

By 1845–1847, the marriage had failed irretrievably and Kemble returned to Europe.

[2]

Separation and divorce

In 1847, Kemble returned to the stage in the United States, as she needed to make a living. Following her father's example, she appeared with success as a Shakespearean reader, rather than acting in plays. She toured the United States. The couple endured a bitter and protracted divorce in 1849, with Butler retaining custody of their two daughters. At that time, with divorce rare, the father was customarily awarded custody in the patriarchal society. Other than brief visits, Kemble was not reunited with her daughters until each came of age at 21.

[14]

Her ex-husband squandered a fortune estimated at 0,000, but was saved from bankruptcy by a sale on 2–3 March 1859 of 436 people he held in slavery.

The Great Slave Auction

, at Ten Broeck racetrack outside

Savannah, Georgia

, was the largest single slave auction in United States history. As such, it was covered by national reporters.

[15]

After the

American Civil War

, Butler tried to run his plantations with free labour, but failed to make a profit. He died of

malaria

in Georgia in 1867. Neither Butler nor Kemble remarried.

[16]

Later life

Kemble's success as a Shakespearean reader enabled her to buy a home in

Lenox, Massachusetts

.

[17]

In 1877, she returned to London to join her younger daughter Frances, who had moved there with her British husband and child. Using her maiden name, Kemble lived there until her death. During this period she was a prominent and popular figure in London society, and became a great friend of the American writer

Henry James

during her later years. His novel,

Washington Square

(1880), was based on a story Kemble told him about one of her relatives.

[18]

Literary career

Kemble wrote two plays,

Francis the First

(1832) and

The Star of Seville

(1837). She also published a volume of poems (1844). She published the first volume of her memoirs,

Journal

, in 1835, shortly after her marriage. In 1863, she published another volume in both the United States and Great Britain. Entitled

Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839

, it included her observations of slavery and life on her husband's Southern plantation in the winter of 1838–1839. It contains the earliest-known written use of the word "

vegetarian

": "The sight and smell of raw meat are especially odious to me, and I have often thought that if I had had to be my own cook, I should inevitably become a vegetarian, probably, indeed, return entirely to my green and salad days."

[19]

After separating from Butler in the 1840s, Kemble travelled in Italy and wrote a two-volume book on this time,

A Year of Consolation

(1847).

[20]

In 1863 Kemble also published a volume of plays, including translations from

Alexandre Dumas, père

and

Friedrich Schiller

. These were followed by additional memoirs:

Records of a Girlhood

(1878);

Records of Later Life

(1882);

Far Away and Long Ago

(1889); and

Further Records

(1891). Her various reminiscences contain much valuable material about the social and theatrical history of the period. She also published

Notes on Some of Shakespeare's Plays

(1882), based on long experience in acting and reading his works.

Descendants

Kemble's older daughter, Sarah Butler, married Owen Jones Wister, an American doctor. Their one child,

Owen Wister

, grew up to become a popular American novelist, writing in 1902 a popular 1902 western,

The Virginian

.

Fanny's other daughter Frances met James Leigh in Georgia. He was a

minister

born in England. The couple married in 1871, and their one child, Alice Leigh, was born in 1874. An attempt was made to run Frances's father's plantations there with free labour, but no profit could be made. Leaving Georgia in 1877, they moved permanently to England. Frances Butler Leigh defended her father in the continuing post-war dispute over slavery as an institution. Based on her experience, Leigh published

Ten Years on a Georgian Plantation since the War

(1883), a rebuttal to her mother's account.

[14]

Death

Her granddaughter Alice Leigh was present when Fanny Kemble died in London in 1893.

Controversy

[

edit

]

While Kemble's account of the plantations has been criticised, it is seen as notable for voicing the enslaved black people, especially enslaved black women, and has been drawn on by many historians.

[21]

As noted earlier, her daughter published a rebuttal account. Margaret Davis Cate published a strong critique in the

Georgia Historical Quarterly

in 1960. In the early 21st century, historians

Catherine Clinton

[

and Deirdre David studied Kemble's

Journal

and raised questions

[

about her portrayal of Roswell King, father and son, who successively managed Pierce Butler's plantations, and about Kemble's own racial sentiments.

On Kemble's racial views, David notes how she would call black slaves stupid, lazy, filthy and ugly, but such views were then common and compatible with opposing slavery and outrage at its cruelties.

[22]

Clinton noted that in 1930, Julia King, granddaughter of Roswell King, Jr., stated that Kemble had falsified her account of him after he spurned her affections.

[23]

There is little evidence in Kemble's

Journal

that she encountered Roswell King, Jr., on more than a few occasions, and none that she knew his wife, the former Julia Rebecca Maxwell. But she criticized Maxwell as "a female fiend" because a slave named Sophy told her that Mrs. King had ordered the flogging of Judy and Scylla, "of whose children Mr. K[ing] was the father."

[24]

Roswell King, Jr., was no longer in the employ of her husband when Pierce Butler and Kemble began their short residency in Georgia. King had resigned due to "growing uneasiness... born of a dispute between the Kings and the Butlers over fees the elder King thought were owed him as co-administrator of Major Butler's estate."

[25]

Before arriving in Georgia, Kemble had written, "It is notorious that almost every Southern planter has a family more or less numerous of illegitimate coloured children."

[26]

Her statements about Roswell King, Sr., and Roswell King, Jr., and their alleged status as white fathers of enslaved mulatto children, are based on what she was told by other slaves. In some cases, individuals relied on hearsay accounts of their paternity, although European ancestry was visible. The mulatto Renty, for example, was "ashamed" to ask his mother about the identity of his father. He believed he was the son of Roswell King, Jr. because "Mr. C[ouper]'s children told me so, and I 'spect they know it."

[27]

John Couper, the Scottish-born owner of a rival plantation adjacent to Pierce Butler's Hampton Point on St. Simon's Island, had had marked disagreements with the Roswell Kings in the past. Clinton suggests that Kemble favored Couper's accounts.

[28]

[

Biographies

Numerous books have appeared on Fanny Kemble and her family, including Deirdre David's

A Performed Life

[9]

(2007) and Vanessa Dickerson's passage on Kemble in

Dark Victorians

(2008). Earlier works were

Fanny Kemble

(1933) by Leota Stultz Driver,

Fanny Kemble: A Passionate Victorian

(1939) by Margaret Armstrong,

[29]

Fanny Kemble: Actress, Author, Abolitionist

(1967) by Winifred Wise,

[30]

and

Fanny Kemble: Leading Lady of the Nineteenth-century Stage : A Biography (1982)

by

J.C. Furnas

.

[31]

Some recent biographies that focus on Kemble's role as an

abolitionist

include

Catherine Clinton

's

Fanny Kemble's Civil Wars: The Story of America's Most Unlikely Abolitionist

(2000). Others have studied the theatrical careers of Kemble and her family. One of these, Henry Gibbs'

Affectionately Yours, Fanny: Fanny Kemble and the Theatre

, appeared in eight editions between 1945 and 1947.

Charles Kemble

(25 November 1775 – 12 November 1854) was a Welsh-born English actor of a prominent

theatre family

.

[

Charles Kemble was one of 13 siblings and the youngest son of English Roman Catholic theatre manager/actor

Roger Kemble

, and Irish-born actress Sarah Ward. He was the younger brother of, among others,

John Philip Kemble

,

Stephen Kemble

and

Sarah Siddons

. He was born at

Brecon

in

South Wales

. Like his brothers he was raised in his father's Catholic faith, while his sisters were raised in their mother's Protestant faith. He and John Philip were educated at

Douai School

.

After returning to England in 1792, he obtained a job in the

post office

, but soon resigned to go on the stage, making his first recorded appearance at

Sheffield

as Orlando in

As You Like It

in that year. During the early part of his career as an actor he slowly gained popularity. For a considerable time he played with his brother and sister, chiefly in secondary parts, and received little attention.

Charles Kemble, by Henry Perronet Briggs. Oil on canvas, before 1832

His first

London

appearance was on 21 April 1794, as Malcolm to his brother's

Macbeth

. Ultimately he won independent fame, especially in such characters as Archer in

George Farquhar

's

Beaux' Stratagem

, Dorincourt in

Hannah Cowley

's

Belle's Stratagem

, Charles Surface and Ranger in

Benjamin Hoadley

's

Suspicious Husband

. His

Laërtes

and

Macduff

were as accomplished as his brother's

Hamlet

and Macbeth. His production of

Cymbeline

in 1827 inaugurated the trend to historical accuracy in stagings of that play that reached a peak with

Henry Irving

at the turn of the century.

In comedy he was ably supported by his wife,

Marie Therese De Camp

, whom he married on 2 July 1806. His visit, with his daughter

Fanny

, to America during 1832 and 1834, aroused much enthusiasm. The later part of his career was beset by money troubles in connection with his joint proprietorship of

Covent Garden

theatre.

He formally retired from the stage in December 1836, but his final appearance was on 10 April 1840. From 1836-1840 he held the office of

Examiner of Plays

.

[2]

In 1844-45 he gave readings from

Shakespeare

at Willis's Rooms.

Macready

regarded his Cassio as incomparable, and summed him up as "a first-rate actor of second-rate parts."

HMS

Fury

was a

Hecla

-class

bomb vessel

of the British Royal Navy.

The ship was ordered on 5 June 1813 from the yard of Mrs Mary Ross, at

Rochester, Kent

, laid down in September, and launched on 4 April 1814.

Fury

saw service at the

Bombardment of Algiers

on 27 August 1816, under the command of

Constantine Richard Moorsom

.

[1]

Arctic exploration

Between November 1820 and April 1821,

Fury

was converted to an

Arctic

exploration ship and re-rated as a

sloop

. Commander

William Edward Parry

commissioned her in December 1820, and

Fury

then made two journeys to the Arctic, both in company with her

sister ship

,

Hecla

.

Her first Arctic journey, in 1821, was Parry's second in search of the

Northwest Passage

. The farthest point on this trip, the perpetually frozen strait between

Foxe Basin

and the

Gulf of Boothia

, was named after the two ships:

Fury and Hecla Strait

.

On her second Arctic trip,

Fury

was commanded by

Henry Parkyns Hoppner

while Parry, in overall command of the expedition, moved to

Hecla

. This voyage was disastrous for

Fury

. She was damaged by ice at the start of the second season and was eventually abandoned on 25 August 1825,

[2]

at what has since been called Fury Beach on

Somerset Island

. Her stores were unloaded onto the beach and later came to the rescue of

John Ross

, who travelled overland to the abandoned cache when he lost his ship further south in the

Gulf of Boothia

on his 1829 expedition.

Legac

In 1956, Captain T.C. Pullen,

RCN

, sailed

HMCS

Labrador

on an expedition through the Northwest Passage. During this voyage

Labrador

recovered two

Admiralty Pattern anchors

on Fury Beach, Somerset Island. The anchors were left there in 1825 by the crews of

Fury

and

Hecla

, together with stores, boats, and other items. The anchors had been a landmark for sailors for 136 years.

Labrador

transported the artifacts to

Halifax, Nova Scotia

, and they were placed in the

Maritime Command Museum

(1961). In 1972,

Fury

'

s anchors were moved to CCG Base Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. In 1981, the anchors were removed to the

Canadian Coast Guard College

at

Sydney, Nova Scotia

. In 1991, the relics were prepared to be part of a popular exhibit. On 6 May 1998, the anchors were donated by the Canadian Forces Maritime Command (MARCOM) to the

Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean

at

Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

,

Quebec

. Currently, the anchors are displayed at the northeastern corner of the parade square.

Fury and Hecla Strait

is a narrow (from 2 to 20 km (1.2 to 12.4 mi) wide) Arctic seawater channel located in the

Qikiqtaaluk Region

of

Nunavut

, Canada. Situated between

Baffin Island

to the north and the

Melville Peninsula

to the south, it connects

Foxe Basin

on the east with the

Gulf of Boothia

on the west. Water flow in the strait is sometimes westerly and sometimes easterly – there are diurnal and semidiurnal components to the flows; tidal and subtidal effects also play a role. The strait provides Arctic Ocean drainage for Hudson Bay via Foxe Basin.

The Strait is named after the

Royal Navy

ships

HMS

Fury

and

HMS

Hecla

, which encountered the strait in 1822 during an expedition led by

Sir William Edward Parry

. Both ships became stuck in ice in October 1821, and remained immobile for eight months. During this time, the expedition learned of the strait from the native Inuit. Two men from the expedition set out with four Inuit on sled to assess the strait. Captain Parry would later accompany another trip to the strait.

The word

diorama

/

ˌ

d

aɪ

ə

ˈ

r

ɑː

m

ə

/

can either refer to a 19th-century mobile theatre device, or, in modern usage, a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as

military vehicle modeling

,

miniature figure modeling

, or

aircraft modeling

.

[

citation needed

]

In the United States around 1950 and onward,

natural history

dioramas in museum became less fashionable, leading to many being removed, dismantled or destroyed.